Part II - The Dark Room Effect:

Or, How to Watch a Horror Movie When You have No Friends

I feel like this is a good time to go back a little bit, to get a little more speculative and philosophical and let this piece breathe. Forgive my indulgence.

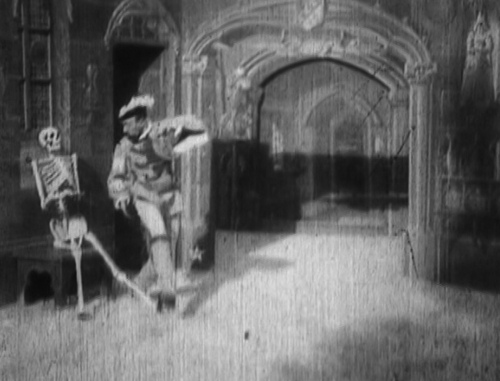

The origins of the horror story in popular culture are impossible to pinpoint, but in a cinematic context they were really informed by literature, as was often the case in early filmmaking. (Early films were treated much like plays, so they often drew from literary and/or theatrical sources.) Silent films dating as far back as the 1890s (Georges Melies's La Manoir du diable (The House of the Devil) is considered the first horror film) built upon the gothic horror literature of more than a century earlier which introduced such iconic characters as Dr Frankenstein, Dracula, Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, and others. Quite lofty beginnings for a genre roundly criticized for being too crass and vulgar.

The origins of the horror story in popular culture are impossible to pinpoint, but in a cinematic context they were really informed by literature, as was often the case in early filmmaking. (Early films were treated much like plays, so they often drew from literary and/or theatrical sources.) Silent films dating as far back as the 1890s (Georges Melies's La Manoir du diable (The House of the Devil) is considered the first horror film) built upon the gothic horror literature of more than a century earlier which introduced such iconic characters as Dr Frankenstein, Dracula, Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, and others. Quite lofty beginnings for a genre roundly criticized for being too crass and vulgar.Now, more than two centuries after the first written horror stories, and a century after the first filmed horror stories, we've gone through nearly every conceivable iteration of these characters and situations... yet audiences keep coming back. Nearly every scenario has been done so many times that we've ventured past cliche into caricature... and all the while, people want more. Audiences continually seek out tales which could disturb and excite them, which could exploit their fears and palpitate their senses... Where does this desire come from? Why do human beings like to be scared?

In my view, our desire to be scared stems from a few intrinsic human qualities. One - our innate mixture of fear and curiosity when it comes to the Unknown, and especially the Unknowable. The idea of the Unknown, whether embodied or disembodied, drives all of drama. We are curious by nature, and we want answers for our questions. The answer can be simple or complex, innocent or foreboding, but we still want to know. In the context of the horror story, this innate desire can be skewed and exploited. Think of the classic cliche: the naive, unsuspecting hiker hears a strange sound in the darkness, and goes to investigate. "What's out there?" "Where did that come from?" A whole host of questions arises from this one simple event, and the multitude of answers yields limitless possibilities for terror. A great horror story takes this concept a step further, producing what I refer to as the Unknowable. How much more terrifying is it to know the answer but not understand it? A perfect example exists in the comparison of John Carpenter's and Rob Zombie's respective Halloweens: the Zombie version set to distinguish itself by trying to explain Michael Myers, to show how/why he became the evil psychopath we know and fear; Carpenter simply took it as a given. It didn't matter how or why he was the way he was, you just had to get away! Which is more effective? Exactly.

Two - great horror stories consistently exploit our social nature, a cinematic phenomenon I refer to as the "Dark Room Effect." Have you ever watched a movie in a crowded theater and thought it was a great movie, only to watch it months later at home and find yourself less than impressed? It's the same reasoning behind the term "infectious laughter": human beings are social creatures, and when in groups, our reactions tend to be heightened. This is precisely why there are so many loud, startling, "Gotcha!" moments in movies - filmmakers are counting on the few people genuinely scared/surprised to infect the rest into feeling scared or surprised. It's audience manipulation, but it works. (Really great movies, of course, do not rely on this phenomenon, but all movies utilize it to a certain degree.) In a horror context, the Effect is heightened even more because darkness by its very nature obscures reality and rouses our curiosity. This is why I love to see horror movies with an audience - they evoke a much more visceral, collective response.

Movie theaters will undoubtedly go by the wayside one distant day; and when they do, I imagine horror movies will not be far behind. It is near impossible to recreate the Dark Room Effect in the cozy confines of a familiar setting; the only effective way to enjoy collective thrills sans a crowded theater is through nothing short of a viewing party. The more people the better, the less familiar the better.

In short, to really enjoy the full horror experience, you need a big, dark, cavernous space full of strange people, pictures, and sounds.

The problem with Rob Zombie's remake is that it splits its time right down the middle between remake and new material. It is as if he wanted to bring something new to the Halloween story, but didn't trust that the hardcore Halloween audience would stand for something totally new. As it stands, the new material feels rushed and the remake lacks the grueling suspense of the original. A lose/lose, if you will.

ReplyDeleteRob Zombie's Halloween does have its strong points: the scenes with young Michael in the asylum are intriguing, the scenes with Michael's mother after he murders the family are heartbreaking, Brad Dourif is excellent. Including Laurie Strode as Michael's sister from the beginning makes it feel more organic to the story as opposed to the deus ex desperation it was in Carpenter's Halloween 2.

That brings me to an ironic point. Your comment about why Carpenter's Halloween is more effective than Zombie's (which is accurate) gets flipped on its head when you start talking about their immediate sequels. Carpenter's Halloween 2, besides being quite inferior in terms of craft, adds an explanation to the Shape's actions which renders the entire first film meaningless. If all Michael had wanted to do was kill Laurie, a person with his physical power and resourcefulness could have done so within minutes. That he spent the whole film stalking people and toying with Laurie now makes no sense, even by the logic of a horror film.

In Zombie's Halloween 2, he is working with new material that is completely his own. What's more, the basis of his film (director's cut, anyway) is a question no slasher film has ever asked before, "what happens to people who survive a slasher film?" What follows is a dark and brutal film, overflowing with rage and anger. It even tries to portrait how Michael views the world, although his visions are the most hit-or-miss parts of the film. I found this film to be damn near a masterpiece, and I have a prepackaged rant about when critics review films for what they think they should be, as opposed to what they are that I will save for another time.

PS. Personal blogs are, by there very nature, indulgent, so if we are reading it, we have clearly forgiven your indulgence, thus making your opening unnecessary.

I'm still trying to squeeze Zombie's Halloween II into my October viewing, but it doesn't look like it will happen. It is one of my top priorities movie-wise, however. If his sequel is as good as you say it is, then that would give him a good-great ratio of one-to-one for his film career, and that would mean both of his sequels surpass his originals - no small feat. And I never actually saw any of the other Halloween films, so while I have no basis for comparison, it sounds like Carpenter really dropped the ball on the original sequel.

ReplyDeleteOverall, I thought Zombie's Halloween was pretty good. It felt a little too "scene for scene" once it got to the remake material, but there are some strong scenes in that film; look for a full review relatively soon.